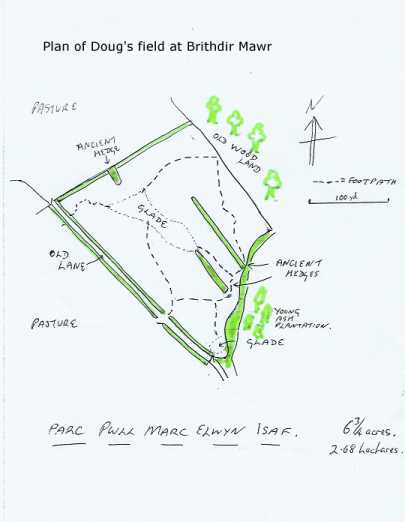

I made a New Year’s resolution on January 1st 1994, to buy a field and start planting a native woodland. Unlike many resolutions, this one came true and has brought me a lot of hard work and happiness. I advertised for land, and nearly bought a field elsewhere, and then Julian and Emma Orbach asked me if I’d like to buy one of the fields on their newly acquired farm, Brithdir Mawr – the rest is history.

I applied for a Woodland Grant, and to get this I had to make a detailed plan and timetable of planting, and the Forestry Commission advised me on the mixture of native trees. I planned to plant about 500 trees each winter for 5 years, to cover 5 acres, with a central glade of nearly an acre.

I applied for a Woodland Grant, and to get this I had to make a detailed plan and timetable of planting, and the Forestry Commission advised me on the mixture of native trees. I planned to plant about 500 trees each winter for 5 years, to cover 5 acres, with a central glade of nearly an acre.

Sessile and pedunculate oak make up about 33%, followed by Ash (20%), birch (17%), hazel (8%), wild cherry, rowan and beech (each 5%). There is a good scattering of hawthorn and holly, and a few crabapples, yew, damson and sweet chestnut. The strong proportion of hazel is concentrated between two ancient hedges where evidence of dormice was found. All the other trees are planted randomly, except for the oaks in groups of around 20-25. This ensures them light in early growth, and means they won’t dominate the field in later years.

I planted the hard way! Clearing a square yard of surface grass or bracken (this is called screefing), digging a hole that would fit the roots, planting and then mulching each tree with a square yard of black plastic, dug in at the edges. The trees were spaced at about 10 feet, and after the first year I avoided rows, to make it more natural.

I don’t think I could have done it all without the tremendous effort of my good friend Angus. It was labour-intensive, but nearly all the trees got off to a good start and the mulches were very good at suppressing weeds and conserving moisture, especially in dry springs. The plastic mulches are nearly all from discarded silage sheets from local farms.

I have not used any chemicals or fertilisers at all. The field is mainly well drained with an acid soil, and was well fenced, with no sign of rabbits. However some creature took a fancy to the growing wild cherries, even biting the tops off one or two, so I had to put guards on them, and later I found that voles were gnawing at the ash trees, so most of these had vole guards put on.

I bought nearly half the trees from a local nursery – Ty Rhos – just a mile away. The rest I raised from local seed (oak, hazel, beech, ash, hawthorn), and a lot I found as seedlings, or were given. Many of the trees are producing their own seed now, and lots of seedling oak, hazel, hawthorn, birch and willow are to be seen. I remove these from the glades and paths, but leave the rest alone.

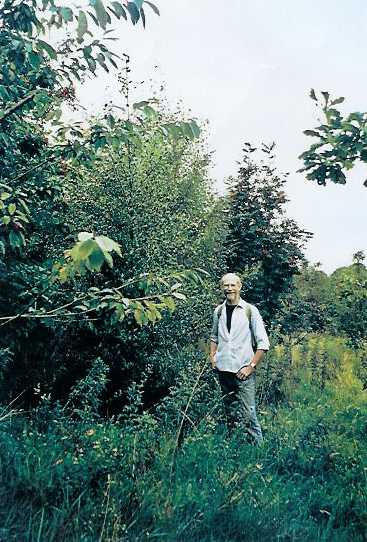

It’s nigh on 10 years since I started planting. Many birch and ash are 25 feet or more, and many oaks are 12-15 feet. I think, on balance, that the trees have done better in the bracken than in grassland. Half the field was tall, dense bracken, and the ground beneath it was virtually weed-free. It likes acid, well drained soil, and its roots don’t seem to compete with the tree roots. It also gives the young trees shelter from the wind, but it must be controlled, as unchecked it makes a tall solid jungle that would kill off young trees.

At first I cut the bracken in the newly planted areas 2 or 3 times in the summer; later I found that I could get away with trampling it once in the last week of June. Cutting it stimulates vigorous regrowth, whereas trampled bracken tries to keep growing from the damaged stems, without much effect.

Cutting the bracken hard in the early years created a problem I did not foresee – it allowed the brambles to run wild, and these smothered some young trees, made access very difficult and in places damaged tree bark through constant friction in the wind. Brambles and bracken do not matter too much once the trees are well above them, and the brambles in particular are useful for insects, birds and dormice. Is bracken part of the food chain? Perhaps, but I noticed, when planting, that there was an absence of earthworms in bracken patches, despite the thick mulch.

There is another problem of my own making – removing the plastic mulches! I dug them in firmly, sometimes adding soil on top, and now it is tough and awkward to pull them up. I started removing them systematically, but I now just do it on an ad hoc basis – I’m probably halfway there.

Other problems – quite a few of the birches have fallen over. I’m not sure why – perhaps the shallow roots have not kept pace with the rapid growth above ground. Where they are still alive I have cut them back to a near vertical shoot. More serious is squirrel damage – our furry friends seem to be attracted to the upper stems of the oak trees, stripping the bark off ruthlessly so that the tree dies off above that point. Apparently, this happens over about 30 days in spring, starting as sap begins to rise, and easing as the sap becomes distasteful due to increasing tannin levels. Some oaks have also been barked lower down – could there be deer around?

There have been pleasant invasions – foxglove, rosebay willow herb, yarrow, orchids, nesting birds, badgers expanding their territory. I’m not sure how the dormice are doing, but they have a lot of good habitat now.

There have been pleasant invasions – foxglove, rosebay willow herb, yarrow, orchids, nesting birds, badgers expanding their territory. I’m not sure how the dormice are doing, but they have a lot of good habitat now.

What of the future? Coppicing could be considered, but I could not manage it myself, and the high proportion of oak would mean a long felling cycle, at least 15 years. I think I will start thinning in a year or two; I’ve read that it’s time to commence thinning once the height of the trees is five times the distance between them. Hopefully this will result in a mixed woodland of well-branched trees, with a fair-sized glade and a grove of hazel. Time will tell!

Doug Bransden

Pembrokeshire, October 2004